Since the passage of Nigeria’s Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act in 2014, the Nigerian LGBT community has lived under constant fear, facing not just legal persecution but also mob violence and social rejection. The law, which criminalizes same-sex marriages with up to 14 years in prison and imposes penalties on those who support or associate with LGBT activities, has created a dangerous atmosphere where prejudice and brutality thrive unchecked.

The law gave homophobia a stamp of legitimacy. Many Nigerians, already holding conservative religious and cultural views, interpreted it as a license to act violently against anyone suspected of being gay. Instead of curbing so-called “immoral acts,” it fueled mob justice, exposing a vulnerable minority to humiliation, abuse, and in some cases, death.

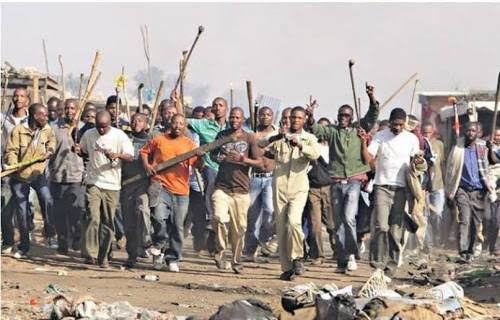

In March 2014, five men in Warri, Delta State, were stripped, beaten, and paraded through the streets after being accused of engaging in consensual same-sex acts. Their ordeal began when an associate blackmailed them, and upon refusing his demands, they were handed over to a crowd that whipped them mercilessly before authorities imposed a fine. Incidents like this highlight how the law has not only emboldened ordinary citizens to act as vigilantes but also blurred the lines between justice and mob rule.

Just weeks later, another attack in Abuja’s Gishiri neighborhood saw a mob drag more than a dozen men from their homes, accusing them of homosexuality. Witnesses recounted that the attackers used sticks, wires, and iron rods, chanting that they were “cleansing the community.” Alarmingly, police officers at a nearby station did not protect the victims but instead beat and mocked them further. For the victims, state protection turned into double victimization.

The pattern of violence has spread across different Nigerian cities. In Benin City in 2022, four young men accused of homosexual activity were paraded in their underwear and chased out of the community. One of them sustained deep wounds on his forehead. The mob declared they would be killed if they ever returned, illustrating how entire communities have taken it upon themselves to enforce exclusion. For many victims, relocation and hiding have become the only means of survival.

These attacks are not random. They are deeply tied to Nigeria’s historical criminalization of same-sex relationships. Section 214 of the Criminal Code, which predates the 2014 law, already criminalized “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” with a sentence of up to 14 years. In northern states governed by Sharia law, punishments can be as severe as death. The 2014 law simply escalated the risks, embedding persecution more firmly in the legal and social framework.

Human rights groups argue that the law has weaponized identity. Instead of tackling issues such as corruption, unemployment, and insecurity, communities are diverting their frustrations toward LGBT people, scapegoating them as symbols of immorality. Activists like Samson Mikel have noted that in cities like Benin, people ignore rampant fraud and violent crime but quickly turn to brutalizing gay men as a show of morality.

The role of law enforcement has also been troubling. In multiple reports, police officers not only failed to protect victims but actively participated in their humiliation. In Abuja, victims beaten by mobs were further assaulted inside police stations. Some were forced to pay bribes or were arbitrarily detained under vague accusations. This breakdown of trust makes it nearly impossible for LGBT Nigerians to seek justice.

International observers have condemned these developments. The U.S. Embassy in Nigeria warned that the law would embolden violence, and subsequent attacks have confirmed those fears. Organizations such as TIERs Nigeria and the International Center for Advocacy for the Right to Health continue to document abuses, calling on the government to repeal discriminatory laws and uphold basic human rights. Yet, little progress has been made, as public discussions about LGBTQ rights remain taboo in Nigeria.

Victims of these attacks often face long-term trauma. Many are forced to abandon their homes, cut ties with families, or flee to other regions or even countries. For those unable to leave, life becomes a cycle of hiding, unemployment, and mental health struggles. Reports of suicides among young LGBT Nigerians point to the silent toll the law has taken beyond the visible violence.

Religious and cultural narratives remain the strongest barrier to change. In many churches and mosques, homosexuality is still described as an abomination, reinforcing stigma in everyday life. Politicians, often wary of losing public support, shy away from any discussion of repealing or amending the law. This silence sustains the climate of impunity for perpetrators of violence.

Yet, not all voices are silent. Nigerian human rights organizations, along with international allies, are advocating for inclusion and justice. Groups such as The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERs) and international commissions have repeatedly urged the federal government to repeal the law, enact policies against hate speech, and align with human rights recommendations from the African Commission.

For now, however, progress remains slow. The reality for LGBT Nigerians is one of daily uncertainty, never knowing when a mob might come knocking, or when a private dispute might turn into blackmail. Living authentically is seen as a crime, while silence and hiding become survival strategies.

The story of Nigeria’s anti-gay law is not just about legal penalties, it is about how laws can normalize hatred and violence. When the state codifies discrimination, it provides cover for ordinary citizens to act with brutality. Until Nigeria revisits this law and fosters dialogue, the cycle of violence will continue, and countless Nigerians will remain prisoners of fear in their own country.